This is an article published on Livewire Markets recently by Matthew Johnson, Portfolio Manager.

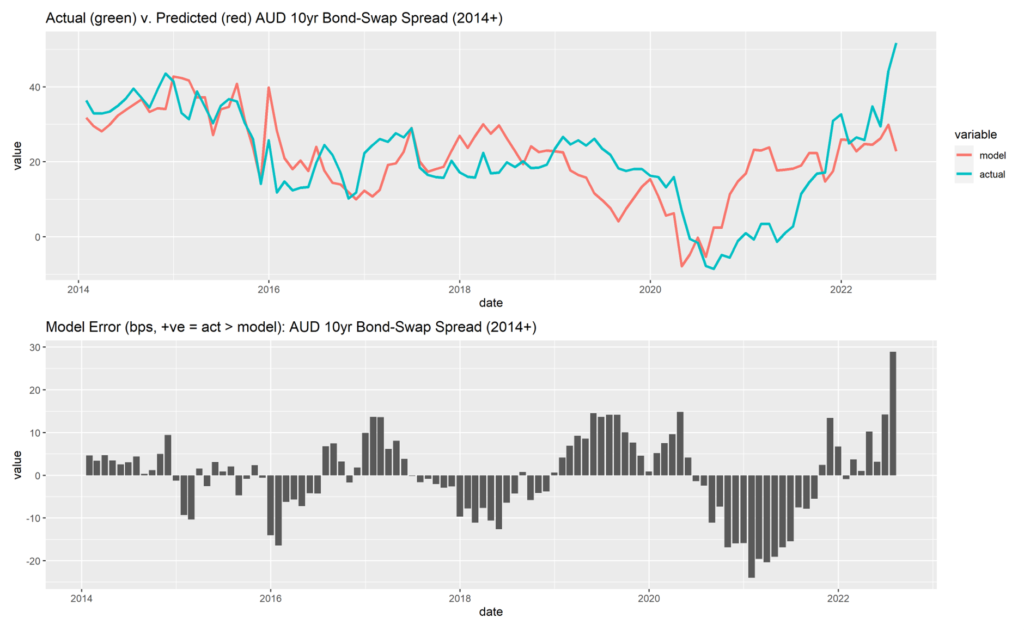

Our fundamental model of Australian swap spreads that we released in December 2021 started the new year well, predicting the early tightening of 10-year swap spreads from the ~30 basis point (bps) down to sub-20bps. Since then, however, it has performed poorly. The unexpected widening of Australian swap spreads could be attributable to a number of factors, including one potentially important variable that was omitted from our bottom-up model: that is, the ‘global’ component of swap spreads. Another frequently cited explanation is a non-fundamental ‘flow’ — large transactions that cause deviations from fair value. The timing of the recent divergence from fair value is consistent with a change in ‘flow’ caused by the RBA’s unexpected failure to defend its Yield Curve Control (April 2024) interest rate peg.

In this note we find that there is indeed a strong global component to Australian swap spreads and that this has been pushing spreads out since mid 2020. Yet, after hitting new record highs in the post-clearing period, our research suggests that Australian swap spreads have overshot the global widening of spreads and are now over 20bps wide of fair value.

The ‘global’ component of swap spreads

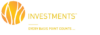

The first half of 2022 has been characterised by the widening of swap spreads in many markets. In particular, there has been a large and concurrent widening of swap spreads – most notably in both Australia and in Europe (see chart below). We judge that this force is responsible for a portion (but not all) of the recent widening of Australian swap spreads.

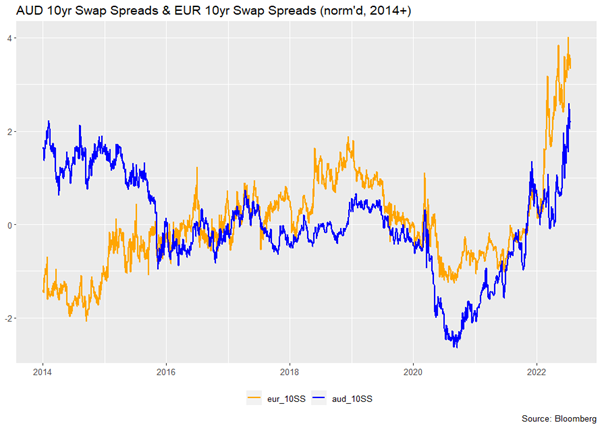

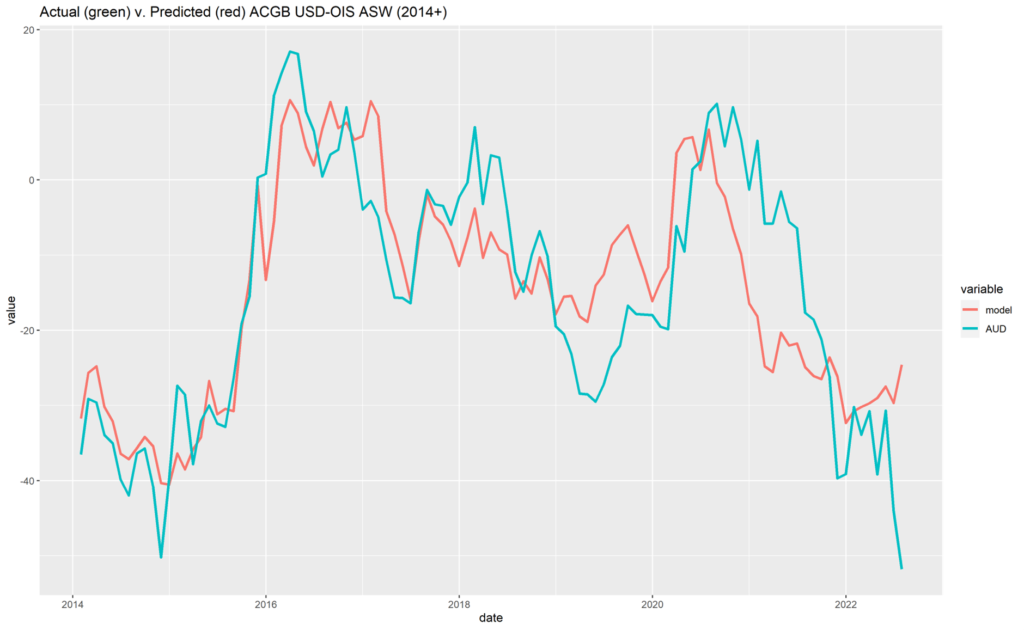

We attribute the globally coordinated moves in swap spreads seem to the investment and issuance activity of global players. It is reasonable to hypothesise that both issuers and investors switch between markets based on their judgements of relative value. When bonds in one market are expensive (relative to USD cash) it is cheap for issuers to issue into that market. That issuance will in turn help cheapen the bonds. Similarly, investors may allocate away from expensive bonds and toward cheaper bonds. The key driver for both decisions is captured by movements in the margin of bonds hedged back to USD cash (we use Overnight Indexed Swaps, or OIS).

As you can see from the below chart, there’s a strong tendency for global bond yields, represented as a margin to USD OIS, to move together. Furthermore, there’s a tendency for outliers to move back toward the average (the thick grey line) over time. Statistical tests confirm the presence of a common factor in a panel of global bonds swapped back to USD OIS in this way (technically speaking, there is a cointegrating relationship between the bonds).

After identifying this global factor in swap spreads, we added it to our Australian fundamental model via a three-step process.

First, we formed a panel containing the hedged-back margin to USD OIS for the following 10yr government bonds: USD, EUR (GER), GBP, JPY, CAD, and NZD. We extracted the first two principal components from this panel. These two factors explained about 62% of the variation of the panel. Broadly speaking, these factors represent the average level of global swap spreads and the difference between swap spreads in the USD-bloc and the EUR-bloc.

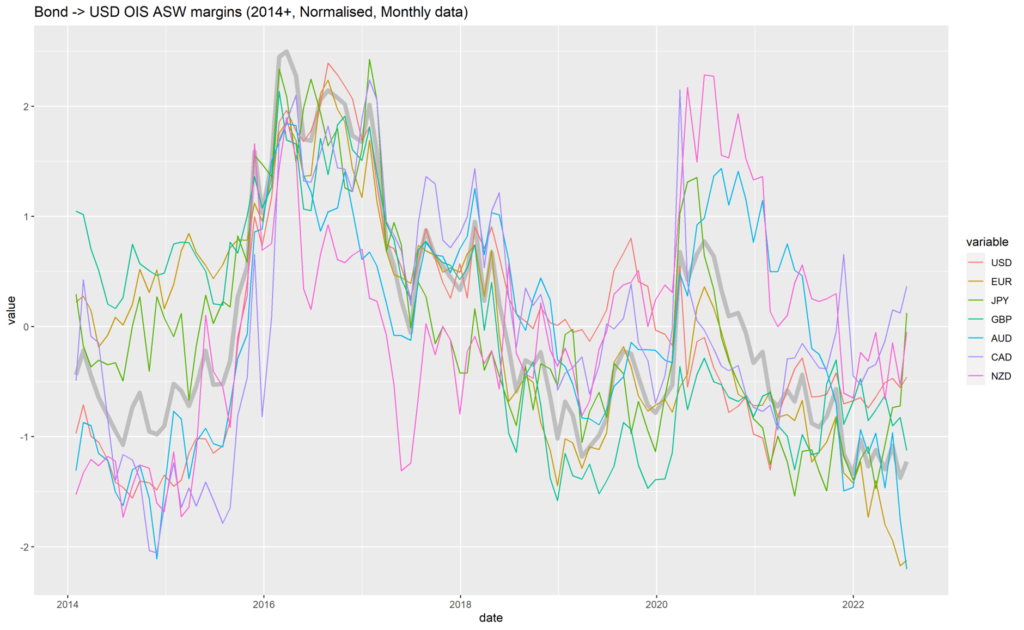

Second, we regress the Australian bond-USDOIS spread on these two global factors. As you can see from the below chart, doing so allows us to explain much of the variation of Australian Bond-USDOIS over the past nine years (we start the analysis in 2014, as there is a structural break due to the advent of centralised clearing).

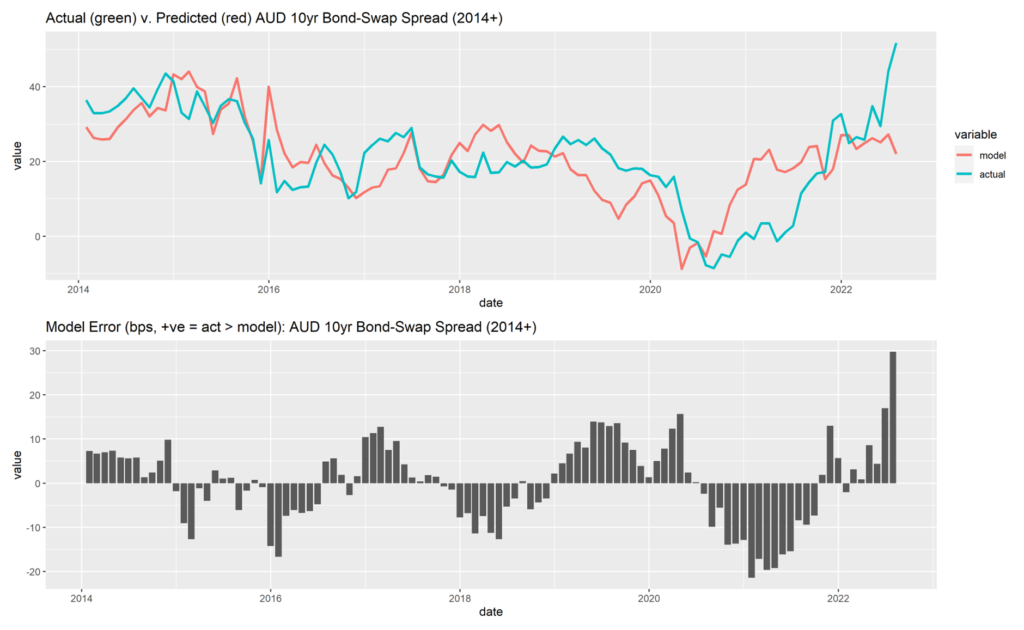

Third, we convert the margin to USD OIS back into an Australian swap spread, using the observed market level of basis swaps (chart below).

What about fundamentals?

In the fundamental model we published in December 2021, we found that movements in issuance and the free-float of bonds were significant determinants of Australian swap spreads. Consistent with that analysis, we find that gross issuance (monthly, as a percentage of the market) and the free-float of ACGBs (the proportion not held by the RBA or offshore) are important drivers of movements in Australian bond-USDOIS, and therefore of Australian swap spreads.

The model below adds these fundamental variables to the above mentioned global factors.

While these variables are highly significant, and comport well with fundamental thinking (and our prior research), they contribute comparatively little explanatory power. A one percentage point change movement in the free float of bonds moves swap spreads by ~1bps (less free float -> wider spreads); and a one percentage point change of gross issuance (as a share of outstandings) tends to move bond-swap spreads by ~2bps in the month it occurs (less issuance -> wider spreads).

The main importance of these results is that we should be alert to issuance events and anecdotes about inflows and outflows from the ACGB market. Market color about ACGB inflows may be particularly helpful as the data is published with a significant lag.

Having said that, even if there were very strong inflows into the ACGB market, it could not explain the ~30bps difference between the observed swap spread and the modelled swap spread. It would require a (clearly implausible) 30ppt increase in foreign ownership of ACGBs.

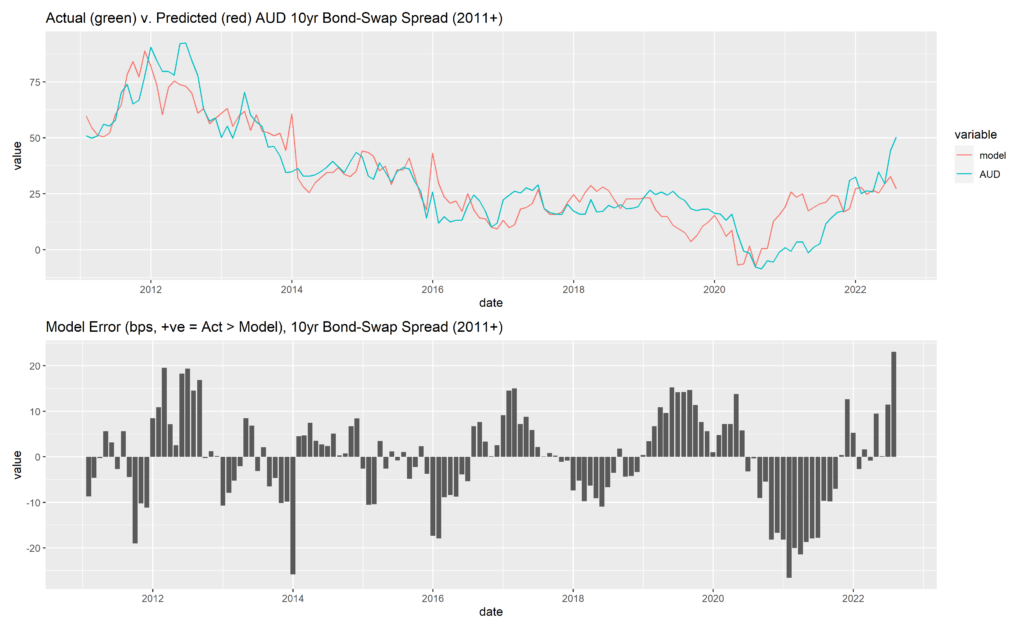

A longer term model

The structure of the market has changed somewhat over the past decade, in part due to the introduction of centralised clearing around 2014. If we model this as a level shift (tighter) of swap spreads in starting in 2014, we can extend the model back to 2011.

Doing so doesn’t change the substance of the conclusion: Australian 10yr spreads are wide relative to our model and the gap to fair value is currently at record wides.

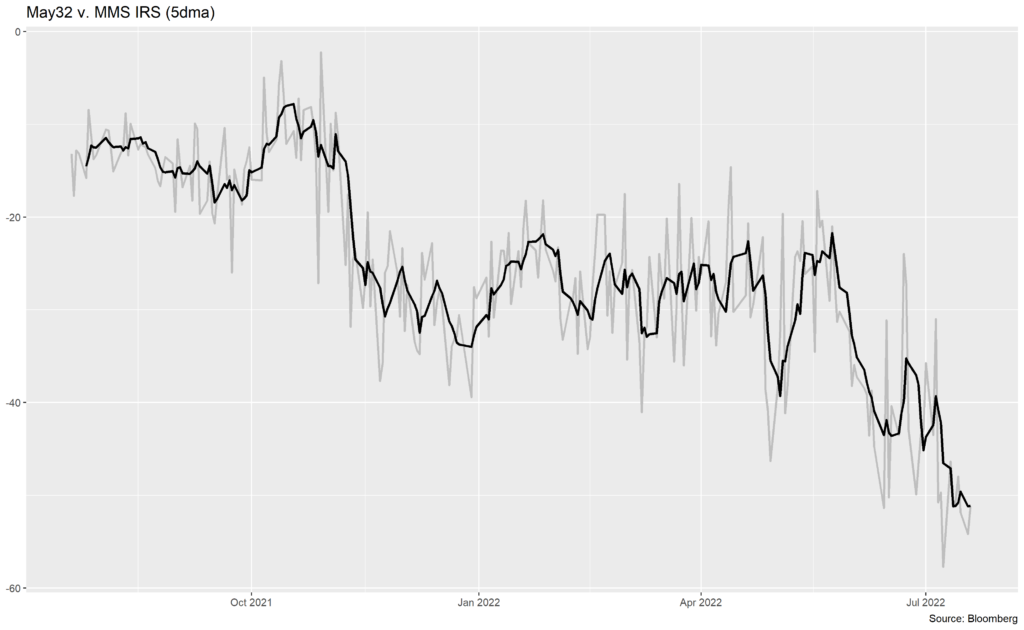

Model fair value (for May32 v. MM IRS), at time of writing, is a little under 29bps v. ~51bps in the market. While this might seem like a long way away, it’s worth remembering that the market traded at this level in May 2022.

An outlook for global swap spreads

The upshot of all this is that the key input into when trading Australian swap spreads is a view about global swap spreads. Looking forward, we expect a cheapening of global bonds relative to USD OIS as the level of interest rates stabilises, central banks unwind their portfolios of Government Bonds, revenue disappoints and issuance increases once again as economies slow (in part due to monetary tightening).

The story of H1’22, in both Australia and abroad, was of better-than-expected revenues, lower-than-expected issuance, and the slow unwind of QE – even as rising yields made government bonds more attractive. As a result, an imbalance between the supply of and demand for government bonds developed.

These forces are now swinging into reverse. A slowing global economy means more (and cheaper) bonds, and the declining share of bonds held by central banks should help global swap spreads to tighten. The acceleration of central bank balance sheet unwinds is announced policy for many central banks, and the Bank of England is likely to announce a plan for outright sales of Gilts in August (joining the RBNZ in active QT) . Further steps in this direction are likely from other central banks.

Aussie spreads are at least 20bps mispriced

Even if we’re wrong about the outlook for global spreads, there appears to be considerable value in Australian swap spreads just now. Relative to global peers, Australian swap spreads are over ~20bps wide of fair value.

We put the large residual down to ‘flow’. A combination of corporate paying and stops drove AUD swap spreads way wider than historical relationships can explain in H1’22. History suggests that corporate fixing flows will ebbs from mid-July. And the earlier strong bid in spreads (that we suspect was a stop out) has already abated.

Conclusion

We found that an omitted variable in our previous fundamental model of Australian bond-swap spreads was a global factor, which is a significant driver of swap spreads over time. Adding this global factor to our model improves explanatory power, however it does not fully explain the recent rise in Australian swap spreads. Even after accounting for the widening of global spreads, AUD 10yr spreads are over 20bps wide of where historical relationships suggest fair value is right now.

While spreads may vary from this model’s projections for some time, we are confident in the long term gravity that fair value exerts. Australian bonds are rich relative to USD OIS, so investors should substitute to cheaper bonds and issuers should look to issue into AUD. This is a patient, but very real, force.

It is notable that the gap to fair value is at all-time wides on both short term and long term models. In terms of timing, we are encouraged by the recent tightening of EUR Swap spreads, and the tightening of model-fair-value. This comports with our fundamental view of the outlook for global spreads and our views around the outlook for global and local Government bond issuance.

Forward-Looking Disclaimer

This article contains some forward-looking information. These statements are not guarantees of future performance and undue reliance should not be placed on them. Such forward-looking statements necessarily involve known and unknown risks and uncertainties, which may cause actual performance and financial results in future periods to differ materially from any projections of future performance or result expressed or implied by such forward-looking statements. Although forward-looking statements contained in this article are based upon what Coolabah Capital Investments Pty Ltd believes are reasonable assumptions, there can be no assurance that forward-looking statements will prove to be accurate, as actual results and future events could differ materially from those anticipated in such statements. Coolabah Capital Investments Pty Ltd undertakes no obligation to update forward-looking statements if circumstances or management’s estimates or opinions should change except as required by applicable securities laws. The reader is cautioned not to place undue reliance on forward-looking statements.